Black History on Long Island

Freedom and Servitude

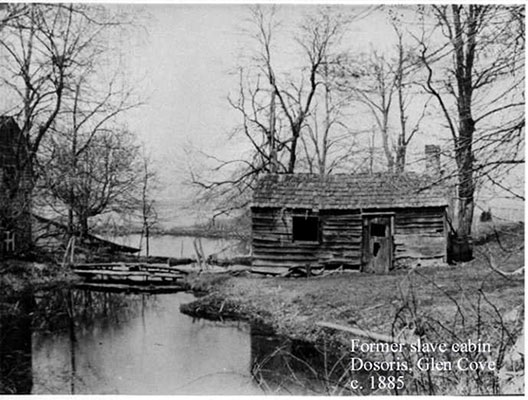

Although there are references to free blacks on Long Island as early as 1657 most of the African Americans on Long Island were slaves until after the Revolution. However, slavery on Long Island was both less widespread and shorter-lived than that of the South. Day workers, journeymen, or family help were more typical.

The climate and geography of Long Island, like that of New England, were not particularly amenable to large-scale plantations worked by permanent slaves. Small farmsteads and long winters made it difficult to feed and shelter large numbers of workers. The typical Long Island household had only two or three slaves and few if any have been found with more than six. [1]

Slavery on Long Island came to an end in 1827

New York State had enacted legislation to abolish slavery in 1799. However, emancipation was neither immediate nor universal. Instead, the terms of the statute called for male slaves to be freed when they attained the age of 28; females, when they reached 25. This resulted in a gradual emancipation that was not complete until 1827, when the last child born into slavery had reached the age of freedom.

Suffrage for African American Long Islanders was introduced in 1821.

The new constitution of the State of New York was enacted in 1821. Under its terms, black males who owned $250 in taxable property were eligible to vote. The same constitution granted suffrage to all white males, regardless of property. Females of both races were denied suffrage until the nineteenth amendment in 1920.

Black Communities on Long Island developed in the nineteenth century.

After the emancipation, many of the newly freed Blacks established communities of their own around the Island. [2]

Some of the early free black communities included the communities of Success and Spinney Hill in the Lake Success/Manhasset area. Freemen also settled in Sag Harbor, New Cassel, Roslyn Heights, Amityville, Glen Cove, Setauket, and Bridgehampton. In addition, many of the free blacks intermarried with the Island's Native Americans and settled on what became the Shinnecock Reservation.

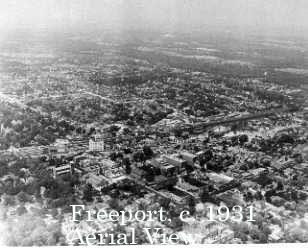

In the twentieth century, black suburbs were established from east to west along the Island. Many of these, like Gordon Heights and North Amityville, were built especially for a black population. Others evolved into predominantly black communities after World War II, when working-class whites abandoned older areas and settled in the newly constructed, but racially restricted GI Bill communities. At the same time the older communities they were vacating experienced an influx of the emerging African-American homeowner class. By the 1960s, communities such as Hempstead, Freeport, Roosevelt, and Wyandanch had become home to a growing black middle class. [3]

Work and Family life among African Americans on Long Island

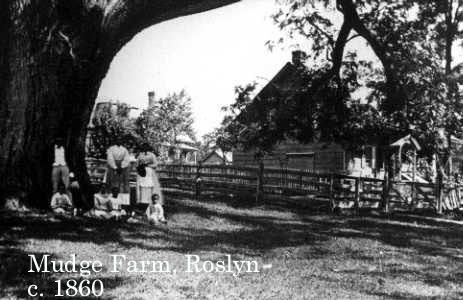

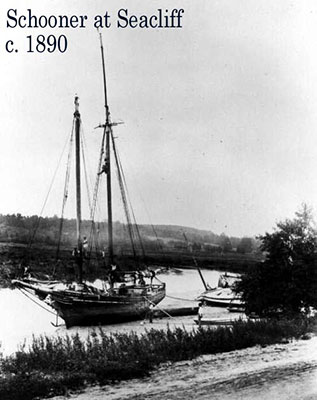

During the antebellum period, the occupations practiced by the freemen in the eastern communities of Suffolk and Queens were similar to those of their white neighbors. Some African Americans served in the shipping and whaling industries, most often as sailors, but also as pilots. Some became captains of their own vessels. [4]

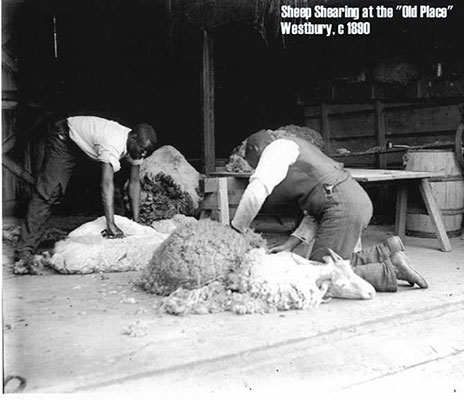

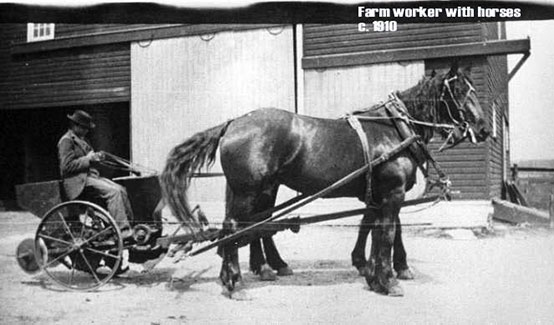

For the most part, however, the men worked the lands, fished and clammed in the bays, or practiced trades as craftsmen and artisans. [5]

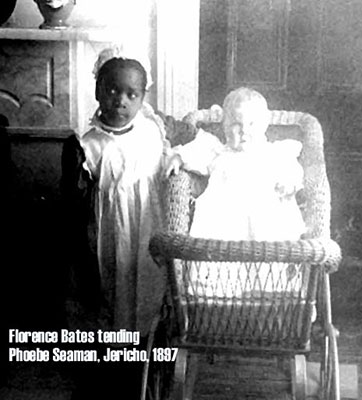

The women engaged primarily in the domestic arts -- cooking and cleaning, weaving, needlework and laundry -- not only for their own families but also for hire in other households [6].

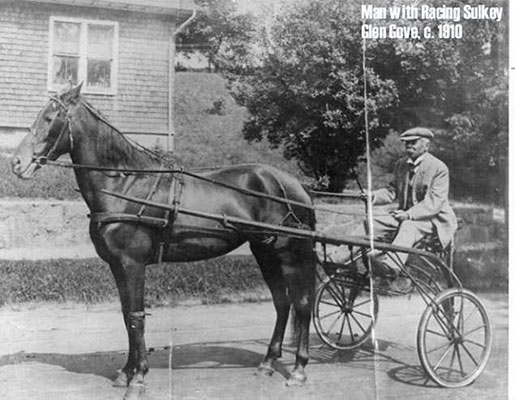

Agriculture, whaling, and fishing continued to be the major occupations in eastern Long Island well into the twentieth century. The residents of Brooklyn and western Queens, due to their proximity to New York City, were more likely to become skilled and semi-skilled workers, from cobblers to blacksmiths and hostlers, these western Long Islanders also turned their hands to the construction trades as carpenters, painters, and masons. Black workers were also drawn to animal husbandry [7] and horse racing [8], where skill was more important than ethnicity. In the years after the Civil War, new occupations were created as the nation became more industrialized. Black workers expanded their skills to meet the new challenges. Women became nurses and cooks [9].

Women founded orphanages and schools, preparing future teachers, musicians and artists, while their husbands and brothers became barbers, coachmen, tailors and waiters.

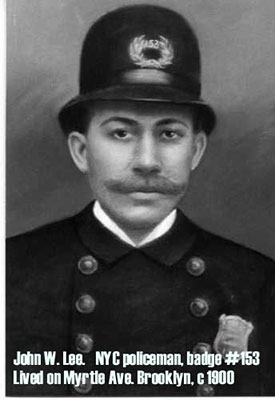

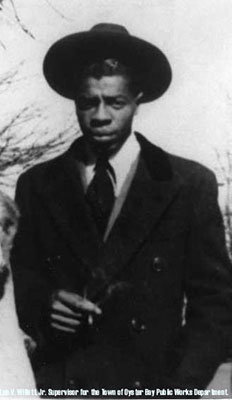

Due to a combination of racism and neglect, opportunities for advancement were severely limited for most of the black population. As a result most found work as day laborers, tenant farmers, or domestics [Day, p.65]. Although the opportunities for economic success were limited, by the end of the 19th century a number of black Long Islanders had become successful businessmen, landowners, and yeomen in their own right. A few engaged in real estate and development, while others joined the clergy. Others began to move into civil service, as policemen [10] railroad workers, and government officials [11].

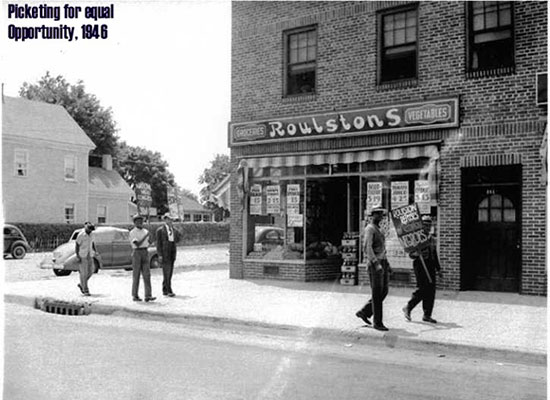

As early as the 1920s, black Long Islanders had protested the practices that limited their access to the fullness of the American Dream. [12]. It would not be until after the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s that opportunities for full advancement would become more widely accessible to the average black worker.

Religion and Education

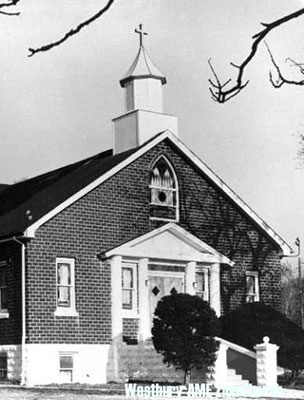

Religious work was not new to the African Americans of Long Island. Centuries of spiritual tradition, dating back to their time in Africa, had supported the black community in slavery and in freedom. After the African Methodist Episcopal Church was founded in Philadelphia at the beginning of the nineteenth century, the AME church became a strong center for the freemen of Long Island. The Bethel AME church in Amityville was founded in 1815, others followed quickly. By the time of the Civil War there were over thirty African-American churches on Long Island, of which twenty-seven were of the AME denomination [13]. In addition, there are a number of black churches within the Baptist, Presbyterian, and Congregational denominations. Many of these early churches remain strong centers of social and religious life in the African-American communities of Long Island

Resources for the Study of African-American History

The Long Island Studies Institute at Hofstra is particularly proud of its recent publications, Making a Way to Freedom; a History of African Americans on Long Island, written by Lynda R. Day and Exploring African American History, Long Island and Beyond edited by Natalie A. Naylor. Both are included in the collections of the Nassau/Suffolk public library system, and are also available for purchase. The books may be purchased through the Long Island Studies Institute at 463-6411, or at many of Long Island's better museum book shops, for example, the Suffolk County Historical Society in Riverhead, the Jamesport Country Store, and the Old Bethpage Village Restoration.

For more research on African Americans on Long Island, visit the Long Island Studies Collection in the Department of Special Collections, Library Technical Services Building, 619 Fulton Avenue [one-half mile west of the main campus] or call 463-6411.