HPIA

Hofstra Papers in Anthropology

Article #1, Volume 4, 2009

Sweden and the Integration of a Growing Iraqi Population

by Sarah Skiold-Hanlin

[An Honors Thesis submitted to The Department of Anthropology, Hofstra University. Honors Committee: Dr. Daniel Martin Varisco, Chair; Dr. Timothy Daniels, Dr. Kari Jensen, June, 2009]

For my mother, father and Brandon

Abstract

The Scandinavian country of Sweden has, in the years since the United States’ invasion of Iraq, seen an increasing rise in the number of Iraqi refugees and asylum seekers. Because Sweden has an ‘open-door’ policy for refugees, it has become the preferred destination for displaced Iraqis migrating to Europe. Resource limitations and difficulties in integrating the new Iraqi populations have resulted in a number of policy changes and social conflicts within the country.

Based on fieldwork conducted in the summer of 2008 and taking into account Sweden’s immigration history, this paper will offer a look into the causes for social conflict and possible future actions on the part of the Swedish government.

Key Words: Sweden, immigration, asylum seekers, Iraqi refugees, integration, Rosengård, Malmö, Vellinge, dispersal policies

Introduction

“One place where many Iraqis have found refuge from the war is Sweden,” stated Renee Montagne, the host of NPR’s Morning Edition. This was her opening line as she introduced the news story titled: Sweden Begins Sending Iraqi Refugees Home. The story aired March 25, 2008. Renee goes on to explain how the “many Iraqis” numbered somewhere in the range of 20,000. A momentary flash of elation followed this opening as my mind began turning over the meaning, estimating its possible weight. Perhaps Sweden, a nation with which I have close family ties, could help rectify the political actions of my country of birth. But like trying to dam the Mississippi River with a box of pop sickle sticks and a bottle of Elmer’s Glue, the flow of refugees fleeing the war in Iraq is far to numerous for one small Scandinavian country to hold. Renee’s voice fervently interjected as she continued washing away my melodic dreams of relief and solution to the persistent humanitarian crisis plaguing so many civilians. “The Swedish government is stopping that flow of Iraqi refugees and sending some back home against their will,” she reported.

The larger story of Iraqi immigrants was handed off to reporter Jerome Socolovsky in Flen, Sweden. Reporting from a Swedish language-learning center filled with “Afghans, Kurds, Iraqis, Somalis and others from the world’s war zones,” he portrays a hopeful beginning for asylum seekers getting a head start on the assimilation process. He interviews one of the students who breaks down as he is forced to relive a horrific bombing that nearly took his son’s life. Though he is now in Sweden, his remaining family resides in Iraq. Yet Sweden is not all that welcoming. Socolovsky goes on to explain that in the recent past this interviewee’s family may have had a promising chance at being granted asylum if it were not for the October 2007 ruling made by Sweden’s Migration Appeals Court (Larson 2008) This ruling declared that there is “no internal armed conflict in Iraq.” Such a ruling made it much tougher for refugees to seek successful asylum under the new restrictive guidelines.

The story touched on the problematic situation from the standpoint of Swedish nationals, government officials, immigrants and asylum hopefuls just the same. It offered no solution to the situation. Though the beginning seemed sympathetic toward the plight of the refugees, its elaboration on the conflict’s entirety did not point any fingers specifically, not at the Swedish government nor its citizens. Nevertheless, the five minutes and fourteen seconds it took to present this kaleidoscope of challenges grabbed my attention as new problems presented themselves at each turn. This was something I wanted to investigate for myself.

Sweden has long been a country that I have idealized. Growing up in the United States as a critical participant has placed Sweden, the country most prominent in my heritage, strides ahead. It has been my opinion that the ‘American way’ and its ostensible refusal to care for its own citizens as well as its ‘elephant in the room’ equality quandary have made it a nation of ‘might makes right’ rather than freedom. My mother, born and raised in southern Sweden, frequented her native land to visit her father, my grandfather. On these trips she would take my brother and I along and introduce us to the wondrous ease of Swedish life. The faux infallible solidarity of the Swedish people and their government’s unending generosity (in reference to its social welfare system and ability to maintain a phenomenal standard of living) became the measuring stick with which all other countries would have to compare.

I had naively overlooked the fact that no country, government, people or individual is without folly. After hearing this story, I began to take a second and more grounded look at the country I admired most. The ability of Sweden to handle the new influx of Iraqi refugees and successfully integrate them into their society is the topic I have chosen to apply my time and efforts to.

Problem

Sweden, today, is faced with serious difficulties surrounding the integration of Iraqi refugees fleeing the dangers of the aftermath that ensued after the US-led invasion in 2003. Choosing Sweden because of its open-border policy for refugees, its generous benefits provided to refugees along with its already established Iraqi communities, more than half of all the EU refugees ended up in Sweden. Asylum applications became backlogged and housing situations well below the Swedish standard of living; the Swedish government has been unable to keep up with the influx of refugees.

The Iraqi communities, located primarily in metropolitan areas, are extremely segregated and many receive little if any exposure to Swedish society. The integration of this particular population has become a national issue as unemployment skyrockets within Sweden’s largest non-European immigrant population.

It is important for refugees to integrate into Swedish society in order to continue their lives despite the devastation caused by the war and the loss of their homeland.

If this community continues to be marginalized, segregated and financially dependant upon the state the likelihood that Swedish economy will not be able to sustain itself as-is, is high. Both the native Swedes as well as the Iraqi refuges are facing permanent cultural changes and must find a way to integrate in order to avoid rising tensions between the two.

Brief Overview of Where and How the Research was Conducted

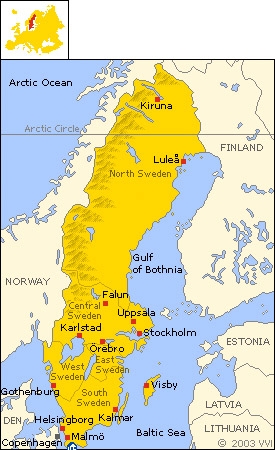

I conducted my field research in the southern most region of Skåne in July and August of 2008. The majority of my interviews with Swedish natives were done in Vellinge municipality. Speaking primarily in English and Swedish, I attempted to draw out opinions and attitudes of Swedes from this area on the issues of immigration and integration.

To gain perspective from that of the Iraqi refugees on the issue, I traveled to the Malmö suburb of Rosengård. I was able to locate this extremely immigrant-dense neighborhood by reading newspaper articles and Internet research before I traveled overseas. I spent nearly everyday observing, engaging and conversing with its local Iraqi population.

I then compiled my interviews and attempted to draw out the main issues from what I had been told and what I had observed. To further my understanding I continued my research back in the states by keeping up with current events from the area, new national policy changes and looking back at, how in the past, Sweden had dealt with the integration issues of previous immigrant and refugee integration issues.

Ideology behind the Swedish Welfare Model

“Universality, solidarity, inclusiveness, equality, social rights and an interventionist labor market policy” - These are the concepts underlying the ideology behind the Swedish welfare model (Steinert/Pilgram 2007). The foundation of the Swedish system is one supported by taxation, so to provide a concrete means of leveling the living differences in conditions for all throughout the country. Tax paying citizens are taxed according to their ability. In turn, the money is then allocated to these citizens based on their need. This is a system in which all tax paying citizens pay according to their ability and, in return, the redistribution is done in hopes of providing the means for individuals to level the differences in living conditions. This objective is based on the principle of an egalitarian society (Swedish Institute 2008). It is the practice of collective solidarity that has been adopted and internalized in this system so that it becomes the safety net for individuals in need. The contribution of an individual is regarded separately from an individual’s right to assistance; many who are being helped by the state have not or are not contributing back to the system.

The system is set up so that no vulnerable group or individual will be left out of assistance on some level. No group should be excluded, whether it is the poor, refugees or homeless, thus making it a form of universal coverage within Sweden. All are considered part of the system with the idea of inclusiveness and equality engrained. Included in the Swedish welfare model is the duty of the public system to “actively search for and identify unfulfilled needs” (Steinert/Pilgram 2007). This is not to say that the public system has not reserved the right to allocate based on individual cases.

The implementation of this ‘no one left out’ Swedish welfare model can be broken down into two levels. The basic level is that of the social insurance system. Citizens earn (by paying taxes) certain benefits through this level. The subsidiary level is that of financial assistance. Individuals are able to appeal to the government for further assistance if they are unable to provide for themselves or their family or if they have a high level of burden to support. This could be anything from a personal handicap to having to support a large family through a single income household.

The Swedish government, in order to facilitate women’s entry into the labor market while subsequently committed to the minimal cost to childbearing and childrearing, developed economic and social policies as incentives for accomplishing this. The expansion of public government subsidized daycare, child benefits, parental leave provisions, parents’ rights to part-time work and other similar measures have in part given the Swedish welfare system the success it has (Hoem 1990). By maintaining the native population while expanding the labor market they are addressing both present and future tax-subsidy issues.

Employment, because of the high level of support provided by the government, is thus an extremely important issue when understanding the government’s perspective on asylum seekers and refugees. A government consigned to provide for its countrymen must maintain low unemployment rates and encourage entrepreneurship if it has any hopes of carrying through with its commitments.

Economic Situation from 1990’s to Start of War

Understanding the importance of high unemployment rates along with the recent immigration waves are key to understanding the most recent actions of the Swedish government. Through all of its efforts the welfare system of Sweden has its successes and shortcomings. In the 1990’s, just around the same time Sweden began seeing the establishment of its first Iraqi communities, the Swedish economy fell into a deep recession caused by a burst in the housing market bubble. The welfare system, which had been growing rapidly since the 1970s, was hit severely as the unemployment rate sky-rocked. This created an unsustainable cycle in which a government, tied closely to the labor unions and corporations, was forced to provide the same benefits for an increasing number of unemployed nationals and incoming refugees while receiving markedly less from its tax-based foundation. By 1993 Sweden hit its record deficit of 12% and in 1994 its deficit surpassed 15% of its GDP. By pulling in labor that would effectively make Sweden more competitive in the IT sector as combined with some smart decision making in the banking sector, Sweden began its gradual recovery (Schön 2006).

During the months prior to the United States invasion of Iraq in March 2003 Sweden’s economic growth slowed to a lethargic dawdle. Progress made in one area was being countered by regressions in another. However, during the spring of 2003, despite any uncertainty surrounding the War in Iraq, there was an upturn in growth. A modest increase in household consumption and production linked to exports (such as motor vehicles and telecommunications products) was greatly influenced by the greater world economic growth. The progression in the world economy, namely that of the United States and Chinese along with Japan’s successful exodus from its era of economic stagnation, was partly responsible for the optimism affecting Swedish consumers. Other positives during this year came from domestic developments in the form of modest wage increases, low inflation, a reduction in Repo rates, and interest-rate cuts by the Riksbank or the Central Bank of Sweden (Hansson 2003).

The period in which Sweden began seeing a new influx of Iraqi refugees was positive as far as economic growth was concerned. However, the labor environment in which most of these asylum seekers would be entering was far from ideal. At this time Sweden was seeing an increase in labor supply (although limited by ill health and an increase in higher education) but a relatively stagnant rate of demand for this labor (Hansson 2004). Though GDP remained on the rise, entrepreneurship and business development was slower to show results. Refugees were entering a competitive labor market with few jobs available and an unemployment rate of 4.7%. (Hansson 2003)

Past Swedish Immigration and Integration History

Up until the start of World War II, Sweden did not have a high frequency of immigrants knocking at their door, as it does now. In fact, Sweden had seen minimal amounts of immigration since its heyday as a major European power during the 17th century when the country primarily saw ‘elite immigrants’ such as merchants, craftsmen, businessmen, and blacksmiths from other European nations (Andersson/Solid 1993). Sweden remained one of Europe’s most homogenous populations until the late 1930’s. Prior to this the most notable population movement took place during the period of 1800-1920. Marked by a notable emigration, largely to the United States, some 1.3 million Swedes left the country (Andersson/Solid 1993). In the 1920’s the United States made significant immigration policy changes. For Sweden the tide began to shift from emigration to an immigration surplus, mostly consisting of returning Swedish-Americans. From this period on, Sweden made the change to a “more permanent net-receiver of international migrants” (Andersson/Solid 1993). Its policy formations concerning immigration can be separated into three initial waves starting after the war in 1945 up until 1984.

Post-war immigration wave 1 (1945-63)

Sweden’s modern immigration history can be broken down into three periods. The first, from 1945-63, was a result of effects from World War II.

After its last war in 1814, Sweden adopted the policy of non-alignment foreign policy at peacetime and neutrality at wartimes. Morally obligated as a country surrounded by neighboring nations, all of whom where involved in the conflict, Sweden kept its borders open to refugees. Though most of the nearly 200,000 refugees to enter into Sweden between 1943-1945 eventually returned home or moved onto the United States, some remained.

The encroaching population shift was also a result of the economic ramifications from the war. Because Sweden’s manufacturing industry was unaffected by the war, demand for Swedish goods after the war rose to a very high level. Unemployment dropped 2% after the war as females began to participate more widely in the labor market. Unfortunately, during the 1930’s as Swedish-Americans returned to Sweden the birth rate dropped dramatically, completely changing the age structure of the society. Thought female participation in the labor market increased there was little hope of keeping up with the labor demand as need for investment goods such as machinery rose. With only an estimated 5.13 million people (Polsson 2008) and a need to fill jobs and keep up with the large tax-base needed to sustain the Swedish welfare state, companies began to identify labor insourcing1 as its only possible means. Thus began the importation of labor as the solution for sustaining the rapid economic growth while curbing inflation.

Immigration began immediately after the war and from 1946 to 1954 a free movement space within Nordic countries (primarily Finland) was introduced. By 1947 a special labor market commission was established by the Swedish government and recruitment of workers in Italy, Hungary and Austria became its main targeted audience for recruitment. The 1950’s brought about the recruitment of citizens from West Germany, the Netherlands, Italy, Austria, Belgium and Greece. It is important to point out that although these non-Nordic immigrants only accounted for about 5% of the total influx during the 1950’s (Widgren 1980) it did mark the beginning of Swedish immigration policy (Andersson/Solid 1993). Due to the large cultural similarities of Sweden’s largest immigrant population (those from other Nordic countries) no one seemed to be taking into account the possible implications and consequences for immigrants, their families and Swedish society in general.

From 1930 to 1960 Sweden had an immigration surplus “with a total of 279,000 people – 39,000 in the 1930s; 134,000 in the 1940s; 106,000 in the 1950s.” (Windgren 1980) Swedish population forecasts did not even take immigration into account until the 1960s.

Post-war immigration wave 2 (1964-73)

Up to this point, the official immigration policy of Sweden was that there was no official immigration policy. The public, however, around this period began to take notice of the demographic change and discussions concerning the implementation of a ‘guest worker’ program came onto the table. Sweden’s laissez-faire approach to immigration and integration did not take a hard line until the trade unions demanded regulations in 1965. This action was in large part a response to the arrival of a large number of Yugoslavs and Turks into southern Sweden, primarily the city of Trelloborg and the economy’s rapid slide into recession. In March 1967, the regulations were officially introduced requiring all non-Nordic immigrants to obtain a work permit, a secure job and accommodation before entering Sweden (Andersson/Solid 1993). This allowed Sweden the flexibility to only allow new labor market participants in when internal capability was in question. However, there were three major groups exempt from these requirements: Nordic citizens (under the 1951 open movement policies), refugees, and close relatives of those residing in Sweden.

Though the regulations addressed the labor unions’ grievances, the Swedish government still continued to recruit outside its boarders. In fact, the immigration rate remained unchanged despite the additional policies. This stimulated the immigration debate among the Swedish public and media throughout the 1960s. With immigration numbers cresting in the late 1960s due to the economic boom, inquiries concerning immigrant assimilation or integration started to be raised (Widgren 1980).

Beginning in 1965, a series of government-implemented efforts began taking shape on how to confront and regulate the many issues involving immigration. The year 1965 marked the introduction of language learning courses for immigrants and refugees. In 1966, the government organized a group that would later propose how information and interpretation of services should be organized. Also, the first municipal organization to take care of immigrant and immigrant related issues was formed; their responsibilities were to organize the reception of refugees. And, finally, by 1968, the government launched an official investigation ‘with the directive to propose a coherent immigrant policy’ (Andersson/Solid 1993).

The second phase of immigration reforms ended with the abolishment of the organized labor market immigration policy of collective recruitment in 1972. Sweden, however, maintained its generous family reunification and refugee policies.

Post-war immigration wave 3 (1979-84)

Although the need for properly guided integration efforts had been realized years earlier it was not until 1975 that the Board of Labor was able to attain Parliamentary endorsement for their integration policy. Principally, the policies where not too far off base from how they currently stands, embodying three primary objectives: equality, freedom of choice, and partnership.

“Immigrants, residing permanently in Sweden were to enjoy the same rights as Swedish citizens (equality), including access to the welfare system. In private life, they could decide whether they wished to assimilate or maintain their distinct native culture (freedom of choice). This also meant targeted language support for immigrant children. Whatever their preference, it should not conflict with essential Swedish values or norms (partnership). Partnership implied, among other things, voting rights in local and county elections.” (Westin 2006)

The 1970s marked an important time for Swedish immigration. Great strides were now being made to meet the dramatically changing demographics of the Swedish population.

A Change: Labor Market Expansion to Asylum Seekers and Refugees

Sweden has for centuries taken in political and religious refugees, although always in low numbers. After 1972, when Sweden effectively terminated its labor immigration policy (this was in part do to the economic recession), a new influx of refugees came at an unprecedented rate. They were non-European political refugees. This first began in 1966, at the request of the UN High Commissioner, when Sweden accepted a group of Lebanon-based Assyrians. Following this initial group, through the 1970s, came Asian Ugandans, Chileans, and other political refugees from South America. This period also saw an increase in ‘spontaneous refugees’ from Hungary, Chile, Yugoslavia, Poland and Turkey (Andersson/Solid 1993).

Unfortunately, the policies (listed in the above section) were created specifically for the need to integrate non-Nordic labor immigrants. This led to the consequent failure of the program. Because Sweden was primarily taking in refugees from the world’s war zones the program suffered from fundamental problems such as its ability to find appropriate language teachers due to shift to refugee immigration three years prior.

A decade after the enactment of the first integration policy, the reins were handed over to a new branch of the Swedish government. The Board of Labor was no longer handling issues of immigration; instead the Board of Immigration was created to take over this responsibility. This time around the integration efforts were ambitiously built on a more practical and grounded foundation: language training, vocational training and dissemination to different towns throughout the country based on available low-cost housing. The municipalities, in which these towns were located, received government subsidies in exchange for their taking responsibility for the practical implementation of the integration effort. Based purely on numbers of refugees accepted into the area, the money was delegated accordingly (Westin 2006).

The program’s faults were exposed early on and it was soon deemed unsuccessful. The program had failed to take into consideration a number of obstacles that led to the creation of a refugee population completely dependent upon the social welfare system. Although housing was available for the refugees, many of the areas in which they were placed were towns with high unemployment, even among native Swedes. Because a loss in numbers of refugees would result in the loss of subsidies allotted to the particular municipality, refugees were not allowed to relocate in search of work elsewhere. As this came to light, the flow of refugees and asylum seekers entering the country continued to stream in without so much as a hiccup. Difficulties plaguing the government persisted as they encountered one municipality after another that refused to take on any more refugees than they already had.

By the end of the 1980s Sweden was in the midst of a population boom it needed to bridle. Not because of high birth rates but rather the previously overlooked practice of serial migration2, it once again was faced with a need to employ stricter requirements for refugees to seek asylum in the country. The effort was futile because the passing of this decision occurred almost synchronously with the collapse of the former Soviet Union and the mass exodus of Iraqis fleeing the oppressive regime of Saddam Hussein and the threat of the Iran-Iraq wars. In a matter of four years (1989-1993) Sweden received some 208,700-asylum seekers from Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo, and the Middle East; most of these were accepted (Gropas/Triandafylliduo 2007). Throughout the entirety of the 1990’s Sweden saw some 177,798 refugees from Iraq alone (Middle East Institute 2008)

In the 1990s, the integration program underwent another revision to allow for “greater flexibility in management” (Westin 2006). Refugees were given the freedom to choose where they wanted to live. This has led to the formation of many ethnically divided communities as refugees have chosen to settle among their own kind. Mostly in major cities, this has added an exorbitant amount of stress to the labor markets in which you see these communities.

This is also when the first Iraqi neighborhoods began to take shape. When in 2003 the invasion of Iraq took place, members of these communities made efforts to reach out to their fellow countrymen. Information about Sweden’s relatively open borders (compared to other western countries) was passed to relatives and family looking for a new country of residence.3

The Iraqi Diaspora and Sweden

The Iraqi Diaspora is the term coined to refer to the native Iraqis who have left their country. In recent history there have been two significant waves of emigration for the Iraqi people that brought them to Sweden. The first wave took place in the 1980s and 1990s during the Iran-Iraq War, the Gulf War of 1990-1 and the Saddam Hussein’s sanctioned post-war government, which forced many Iraqis to leave the country. The second was caused in large part by the 2003 US led invasion of Iraq. During both waves of emigration a great number of Iraqi expatriates chose to settle in Sweden.

From 1980 to 1988, after a long history of border disputes and the fears of a Shia insurgency by the Sunni-lead Iraqi government, Iraqis suffered the Iran-Iraq War. During the war the loyalty of some Iraqi Shia was doubted by the Baathist Arab regime. As a result nearly 30,000 Iraqi Shia were deported to Iran (Gibney/Hansen 2005). Later, some of these displaced Iraqi refugees moved to Europe with hopes of being granted asylum.

By the end of the Iran-Iraq War in 1988 the Iraqi government was all but bankrupt. Despite pressuring by Saddam Hussein, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait refused to forgive the debts owed to them from the war. Iraq accused Kuwait of ‘slant-drilling’ across the Iraqi border into their Rumaila oil field. They also accused Kuwait of violating OPEC quotas by driving down the oil prices. This form of economic warfare, as the Iraqi Government labeled it, had cataclysmal effects on the Iraqi economy (Marr 2004).

After attempts by the US State Department to dissolve the conflict Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. The UN Security Council quickly condemned the invasion and placed the Iraq economy under severe international sanctions. The economy effectively collapsed under the sanctions, which gradually led to the destruction of Iraq’s infrastructure and local resources. This resulted in a countrywide emigration from all sects of Iraq to neighboring countries such as Jordan and Syria. In addition, Iraqis fled to parts of Europe and North America. Expatriates consisted of true refugees as well as those who were merely unhappy with the economic opportunities within the country and went in search of something better abroad (Gibney/Hansen 2005).

Religious, economic, ethnic and sectarian schisms led to the continuation of the exodus throughout the 1990’s. Sweden, with its liberal refugee policy and generous welfare benefits appealed to many Iraqis during this first wave of migration (Gibney/Hansen 2005). From 1980 through 1994, Sweden, who before 1980 had only 500 Iraqis, welcomed more than 20,000 Iraqis in the country (Andersson/Solid 2003).

Mostly settling near their point of entry, Iraqi communities were established most strongly in the Swedish city of Södertälje and the Malmö suburb of Rosengård.

In 2003, the toppling of Saddam Hussein’s Baathist regime by US led forces created the first diaspora of the Twenty-First Century. To date, it is estimated that some 4.7 million Iraqis have been displaced; an estimated 2 million refugees have fled the country, mostly to neighboring Jordan and Syria (Margesson/Bruno/Sharp 2009). For those who have fled to Europe, more than half have ended up in Sweden. With lax refugee policies and already established Iraqi communities from the first wave of the diaspora, it is no wonder why so many flocked to the Scandinavian country of only nine million residents.

It is unknown how many of those who have left Iraq, under forced, voluntary, political or economic migration, plan to return to the country. Years away from Iraq may result in the establishment of a permanent residence outside the country. Those who do return will likely be met with a changed political agenda from those who have remained local under years of suppression and current political turmoil.

Swedish Dispersal Policies

During Sweden’s period of company-run labor immigration immigrants were dispersed according to the specific job in the specific location of the country. This allowed for a variance in where the new populations would settle. This meant that not just major cities but small rural towns and urban areas also took on the load of new people. Refugees, however, predominantly remained near their point of entry such as airports and ferry harbors in southern Sweden. The problem persisted as labor immigration ended and refugees became Sweden’s primary immigrant population, concentrating primarily in and around the Stockholm and Malmö region. The table below, based on police district data, offers only a glance at the geographical pattern of refugee settlement but if useful in its indications for the 1970s and early 1980s.

Table 1: Refugee files by police districts, September 1981

| Regions |

Number

|

%

|

| Stockholm (Stockhom, Uppsala and Södermanlands County) | 2,664 | 48 |

| Malmö (Malmöhus and Kristianstads County) | 1,106 | 20 |

| Gothenburg (Götenborg and Bohus, Hallands and Älvsborgs County) | 741 | 14 |

| Rest of Svealand (Västmanland, Värmland, Närke and Dalarna County) | 254 | 5 |

Rest of Götaland (Östergötalands, Jönköpings, Kronobergs, Kalmar, Gotlands, Blekings, and Skaraborgs County) |

563 | 10 |

| Norrland (all five northern counties) | 1883 |

Source: SOU (1982:49, Appendix 8, Table 1, p 372) (Andersson/Solid 2003)

Throughout these two decades housing for refugees is continually brought up in reports. The 1980 Commission on Immigrant Policy report, in particular, addresses the issue of ‘waiting refugees’ or persons waiting for a decision on their application for permanent residence. The Commission report mandates that “Although it is not a result of immigrant policy considerations, the municipalities have the responsibility for taking care of waiting refugees” it continues on to say: “Waiting refugees are very unevenly distributed over the country, which implies that some municipalities carry a large share of the responsibility” (SOU, 1982:49, 226) It goes on to attribute the imbalance to the residency decision to the existence of fellow countrymen in an area (with a relative or friend) the naturalness of many remaining near an arrival site and the educational opportunities (Andersson/Solid 2003).

It is important to note that Table 1 (above) indicates that approximately 80% of the refugees settled in the three metropolitan areas that already house over 50% of the Swedish national population. This in turn flipped the previously better labor market participation rate of immigrants to lower than that of the nationals. This took a toll on local economies, although it had little effect on the national economy. Even though foreign citizens had a lower labor market participation rate, the age structure of these foreign groups proved advantageous because they raised the overall rate of labor market participation (Andersson/Solid 2003).

From the mid-1980s on, the objective was to steer refugees away from metropolitan areas. Based on the refugee conditions in the early 1980’s, policies were established to try and spread the responsibilities of municipalities out evenly. This was not set up to handle the increased wave of refugees that arrived in 1984 and The Working Group with the Responsibility for Refugees (with the Swedish acronym AGFA) spent much of there efforts negotiating with central and southern municipalities they deemed qualified to handle the housing, job and educational needs of the incoming refugees.

Numerous plans and phased integration proposals were made, tried and failed throughout this period involving efforts to include smaller less labor-optimistic municipalities and larger ones alike. By 1987 most municipalities agreed to participate in the reception program.

During Sweden’s struggle to handle the increasing influx of predominantly non-European refugees, the gap and tensions between the native and immigrant population with respect to the cultural and religious dissimilarities continued to grow. By the end of the 1980s, Europe, particularly Sweden, was seeing refugees flooding in from Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, Turkey, Eritrea, Somalia, Kosovo and several other former states of Eastern Europe. This added to the heavy load Sweden and its municipalities would have to carry and the waiting time for decisions only increased.

Especially at the beginning and throughout most of the years it remained unchanged (1985-1994), somewhere between 270 and 280 municipalities agreed to participate in the ‘Sweden-wide strategy’. This was a strategy in which refugees would be dispersed proportionately, with respect to municipal capacity, to many but not all Swedish municipalities. The numbers of refugees that flooded into the country, however, during this time were far more than anticipated or predicted and under the stress many municipalities began rejecting requests purely on the basis of lack of adequate housing. Eventually the added stress on the economy also forced the decision to allow those still waiting for a decision to find work.

Astoundingly, the Swedish Migration Board (with the Swedish acronym SIV), having run only eight refugee camps in 1985, increased its number of camps to 290 by 1993 (Westin 2006). Attempting to keep up with asylum immigration numbers proportionate to that of World War II, the war in former Yugoslavia sent tens of thousands of refugees to Sweden’s boarders. Due to economic stagnation and the oncoming recession, the refugees entering the country between 1991 and 1993 had little opportunity of finding work. The SIV, in attempts to lessen the economic burden on the economy and municipalities, implemented policy changes to make it more difficult for refugees to enter the country by scrutinizing applications more carefully and requiring a visa for people coming from a ‘refugee-producing country’.

As immigration issues became more and more politicized throughout the 1990’s issues of morality were put on concerning the appointment of a refugee’s placement. From July 1, 1994 on refugees were given the right to arrange their own accommodation if desired. This proved to be an enormous change for better and worse. With more than half of the refugees choosing this option the placement time for housing was cut down dramatically, thus reducing costs for the state. Unfortunately, the resulting situation turned out to be extremely burdensome on the metropolitan areas as most tended to flock to areas in which they would be among their fellow countrymen.

After 1994 until the Iraq War and end of Saddam Hussein’s regime the immigration numbers dropped dramatically. The most notable change prior to the 2003 invasion of Iraq by the United States was the division of responsibility between the SIV and the Swedish Integration Board (SIB) in 1997. The SIV, Sweden’s central governmental authority for aliens’ affairs is responsible for:

“- permits for people visiting and settling in Sweden;

• the asylum process, from application to a residence permit or to a voluntary return home (återvändande);

• citizenship affairs;

• helping out with voluntary return migration (återvandring);

• international work in the EU, UNHCR and other collaborative bodies;

• ensuring that all the relevant public authorities work together satisfactorily.”

(Andersson/Solid 2003)

The responsibility of communicating the three goals of Swedish integration drawn up by the Swedish government and parliament discussed previously in this section (Equality, Freedom of Choice and Partnership) has been handed down to the SIB.

“According to the government and parliament, the board shall:

• monitor and evaluate developments in society from an integration policy perspective;

• promote equal rights and opportunities for all irrespective of ethnic and cultural background;

• prevent combat xenophobia, racism and discrimination (where such issues are not dealt with by some other public authority);

• further ethnic and cultural diversity in the various spheres of public life;

• seek to ensure that local authorities and properly prepared and equipped to take in people in need of shelter or people granted asylum or residence permits on humanitarian grounds, and where required to help out with municipal settlement;

• seek to ensure that newly arrived immigrants’ need of support is properly met as well as their need for specially tailored community information;

• be the decision-making body in respect of government grants to local authorities and county councils;

• provide funding for organizations active in the integration field;

• ensure that appropriate statistics are compiled;

• promote a closer understanding of the issues in the integration policy field overall.”

(Andersson/Solid 2003)

Since responsibilities of immigrant and refugee reception, placement and handling have been delegated between these two boards, many evaluations and studies have been conducted on their effectiveness as well as the effectiveness of the former ‘Sweden-wide’ policy. The final report, conducted by the Commission on Immigrant Policy in 1996, concluded that the overall goals in regards to the reception of immigrants had not been met. This was mostly concluded because the unemployment rate among immigrants was high even after the completion of the 18-month introductory program. Few immigrants had even achieved financial independence within three to four years of having been in the country.

In 1997, the SIV released a comprehensive self-evaluation where they too admitted failure within the program. They cited a lack of understanding in what is necessary to successfully integrate a fragmented population. A lack of knowledge about the refugees, municipalities and everything in between made it very difficult and led to more than half of all the refugees leaving their receptive municipality within two years of settling (SIV 1997). It was concluded and eventually proposed by the SIV that more individual oriented receptions where necessary to make the integration process more successful from a cultural and fiscal perspective.

A report, conducted by economist Mats Hammarstedt for the SIB in 2002, found that it is more expensive for the state to support refugees in metropolitan areas (Anderson/Solid 2003). The cost of living in metropolitan areas is, on average, nearly a third higher than that of manufacturing or agricultural locations.

The higher cost of living in metropolitan areas is attributed to past integration failures into the labor market. In 2000, 50% of Sweden’s refugee cohort was partially if not fully dependant on social security provided by the state (Hammarstedt 2002).

Summary of Past Immigration Difficulties and Trends

Sweden’s recent immigration history ran into many difficulties with the introduction of immigrants that came from areas that varied vastly from the cultural, linguistic, religious and idealistic norms of its natives. As Sweden closed its doors to guest workers while keeping its doors open to refugees and asylum seekers, it realized a need to develop a comprehensive integration strategy. Many failures to successfully maintain social and economic stability pushed Sweden to remain open to reform and new approaches.

The ‘Sweden-wide’ policy placed refugees within municipalities who agreed to take responsibility for the reception, placement and integration of refugees in exchange for state provided subsidies. This strategy was implemented in order to battle the substandard living conditions many refugees had to live with due to housing shortages in the metropolitan areas they typically chose to settle in. Alleviating the stress on these areas, nearly all municipalities chose to participate in the program and it was extremely successful in dispersing the unanticipated quantity of refugee cohorts entering the country at the time.

This policy was viewed with skepticism by humanitarians who believed that it was wrong to deprive people of the right to choose where they wish to settle. In 1994, due to dissension among parliamentary officials on the policy as well as the realization that secondary migration4 was taking place regardless of where immigrants where originally placed, the policy underwent a reform. The policy changes allowed refugees the option of choosing where they would like to settle and only if they opted not to do so would they be placed.

The reform became extremely problematic for metropolitan areas as refugees flocked to the areas that already had established communities with their fellow countrymen. The program was deemed unsuccessful as these areas saw unemployment and dependency on the state (even after several years in residence) skyrocket.

The failures of these and other past policies have influenced the more individualistic approach the SIV is now attempting to take in receiving, placing, and integrating refugees. The tremendous task of doing so successfully is, unfortunately, awash with inherently obstructive variables. The volume of refugees Sweden may receive from year to year is extremely unpredictable and varies wildly. It is also unknown from what region of the world refugees will be fleeing. Therefore, it is difficult trying to keep up with not just the volume but also the implementation of comprehensive receptive programs and staff sufficiently prepared to handle the particulars of language, culture, education and religious practices. Further, the economic situation weighs heavily on Sweden’s receptive resources. These can be anything from jobs to housing.

The state of immigration policies in Sweden leading into the current Iraqi refugee situation this thesis is addressing is one in which many mistakes have been made and learned from. However, the ethnic residential segregation that has come from Sweden’s inability to effectively disperse prior waves of refugees has created a huge roadblock in the integration process. Finding a way to adequately disperse the ethnic population is crucial to leveling the standard of living across all lines, especially that of ethnic diversity.

Rosengård: Suburb of Malmö

Rosengård is a suburb of Sweden’s third most populous city, Malmö. Rosengård, though not home to the highest population of Swedish Iraqis5, has had a long-standing Iraqi community that has attracted those coming to Sweden from its most recent war. A neighborhood built in the 1960s and 1970s to help resolve Malmö’s shortage of cheap housing, Rosengård was immediately seen as a place to house refugees arriving in the southern port city at this time.

In December 2008 the suburb was reportedly home to 22,262 residents, nearly 3,300 of them Iraqis. About 86 percent of the suburbs population are first and second generation immigrants representing 111 different countries. The population is rather young with 35 percent under the age of 20 and only 6 percent over the age of 70 (Malmö Stad 2009).

In Rosengård, the streets are rather calm despite the not all together uncommon siren of fire trucks rumbling down Ramelsväg. This is because the towering 1960’s style apartment buildings that loom over the neighborhoods are overcrowded. According to Sweden’s overcrowding standard, more than two to a room, 38 percent of the children in Rosengård are raised in these conditions. This is compared to the entire city of Malmö in which only 11 percent of the children do (Malmö Stad 2009).

The population here is an extremely mobile one. Between 2002 and 2006 some 9,800 residents moved into the city, while 10,500 left. This is nearly half of the entire population of Rosengård (Malmö Stad 2009). The unemployment rate here is extremely high. Only 37 percent of the population in 2004 had full time jobs while the other 63 lived off of state-provided welfare (Malmö Stad 2009).

Issues raised by the Swedish government

As a country of refuge for those fleeing the world’s conflict zones for over half a century, the Swedish government has developed a unique ideology on immigration policy with high expectations. The ideology of the Swedish welfare model stresses qualities such as universality, equality and inclusiveness for all its citizens. Unfortunately, in reality, actualizing this has proved extremely difficult. In the case of Iraqi refugees fleeing the most recent war, Sweden has been numerically outmatched. The tidal wave of Iraqis that crashed onto Sweden’s shores, estimated at around 80,000 since the war began, sent the SIV and SIB’s heads’ reeling. Housing and job shortages have pushed municipalities bearing the most weight to their breaking points and caused the government to fall short on many of its promises. Sweden has been forced to tighten many of its immigration and asylum policies and is considering making other changes to help alleviate the stress on the most affected municipalities. Also, knowing its limitations, Sweden has repeatedly appealed to other EU nations to help bear the burden of the humanitarian crisis. The government’s desperation for aid in this issue is apparent and has a big hand in what happens to the Iraqi immigrants now and in the future.

Overextended: Sweden’s Struggle to fulfill its Promises

Iraqis fleeing the conflict and persecution brought on by the US lead invasion of Iraq flocked to Sweden. Given the choice of where to settle, after Sweden eliminated the ‘Sweden-wide’ policy, most have settled in the metropolitan areas of Malmö and Stockholm with friends and family. Even those without connections to these locations chose to go there because both areas have established Iraqi communities in which these new refugees can be among their fellow countrymen. Sweden has repeatedly issued statements and amended its immigration policies to ensure that all immigrants are given nearly the same rights as Swedes. This includes access to the State’s welfare system and equality of life.

The reality of the current situation, however, is far from what the government has promised. The shortage of housing has led to severe overcrowding. Fires are a frequent result of this overcrowding along with the quickness in which illnesses spread among these communities (Malmö Stad 2009). Integration resources, meant to help immigrants become part of the society but more importantly the labor market, are overextended. Language courses, schools and job training courses are full. Unable to obtain a job without proficient Swedish language skills and jobs within the community scarce, the majority of the population is unable to achieve financial independence. Due to the nature of the Swedish welfare system, the municipalities hosting these communities have taken extreme blows to the health of their economy. Reliant on tax dollars6 from workers is necessary to support those in need, but does not work if there are too few contributing to the state while living off of it.

Making Changes to the Immigration Policy

Prior to most recent Iraqi influx the last major immigration policy change took place in 1997 with the division of responsibilities between the SIB and SIV. In the years that followed the invasion of Iraq, as the refugee numbers continued to climb, municipal and state resources were stretched thin. This resulted in the Swedish government taking a harder line on those allowed to enter the country under refugee status.

In July 2006, the SIB issued a statement saying that Iraqis who are seeking asylum must be able to prove they face personal danger in their homeland to avoid being sent back. This was based on three immigration court rulings that found that the situation in Iraq was no longer an “internal armed conflict”. Instead the ruling resulted in the situation being classified as “difficult circumstances” (The Local 20072). Dan Elliasson, the immigration service head said, "If they are not personally threatened or harassed, they cannot remain in our country" (The Local 2008). The board claimed that the situation in Iraq did not warrant automatic permanent residency approval because Iraq was no longer engaged in full-blown warfare (The Local 20072). This decision was met with a great deal of controversy as those who did not meet the requirements as deemed by the SIB would be sent back to Iraq.

Though successful in slowing the influx of Iraqi refugees, the policy change did not give any immediate relief to the overcrowded and overextended cities and municipalities. This prompted Tobias Billström and the Swedish Migration Board to support a forced resettlement of refugees. On April 6, 2009, the Ministry of Justice issued a press release, following up on a letter that had been sent, initiated by Sweden, to other EU member state that did not have a refugee quota. It contained the following statement:

“Resettlement is a good and efficient instrument to use in order to offer people in need of protection shelter in another country. The EU has taken steps in the right direction when it comes to resettlement, but in order to raise awareness for the need for resettlement, I now invite my colleagues in the Council to join me to participate in a visit to one of the Swedish Migration Boards resettlement missions to Jordan, says Minister for Migration and Asylum Policy, Tobias Billström.” (Government Offices of Sweden 2009, 7)

In order to avoid the creation of Iraqi ghettos, the forced resettlement of refugees has been put on the table. There have been many ethical questions raised on the issue, though a decision has yet to be made.

Sweden’s Appeal to the EU

In February 2007, Sweden’s migration minister Tobias Billström pressed the other EU member states to take on more responsibility for the Iraqi humanitarian crisis. Sweden at this point had taken in more than half of all the refugees who had fled to Europe. Writing in Svenska Dagbladet, Sweden’s largest newspaper, Tobias Billström and Europe minister Cecilia Malmstöm argued, "there must be solidarity between EU member states, so that more of us share responsibility for sheltering refugees" (The Local 2007).

Jesus Carmona, spokesperson for the European Commission’s Directorate of Justice and Home affairs, responded to Sweden’s demand by saying that there may be no way to divert the flow. Under the EU directive, the country that receives the asylum application is responsible for handling it. It would be up to the other EU member state to voluntarily accept the responsibility, as well as, agreement receive an agreement from the asylum seeker to change its country of application (Edmonds 2007).

Since Sweden’s appeal to the EU for help there has been little change. However, by 2010, the EU hopes to have finalized its European immigration pact “which seeks to balance calls for stricter control of migratory flows with respect for developing countries and the human rights of asylum seekers” (EurActiv 2008). In other words, spearheaded by the French EU Presidency, the pact is aimed at shaping a common European approach to both legal and illegal migration. There are, however, no Swedish position holders on the committee.

Issues raised by native Swedes

The bulk of my interviews conducted with native Swedes were done in one of Sweden’s southernmost municipalities, Vellinge. Located in the Southwestern most region of Skåne, it is primarily a rural agriculture based municipality with the majority of its employed population commuting to the Malmö municipality. With a municipal population of 32,843 in 2008, Vellinge has an 80.5 percent employment rate among it population aged 20-64, the highest in the region. This is compared to Malmö who has the lowest employment rate in the region at 63.9 percent. Statistically, Vellinge has the second highest income per person in the region and boasts the fourth highest in the kingdom (Vellinge Kommun 2008). According to the Fokus magazine rankings of best municipalities to live in 2009, Vellinge placed second (The Local 2009). The judgment was based on a measurement of 30 different criteria including, health, crime, taxes, and equality.

Vellinge has a history of conservative voting when it comes to immigration policy. It is one of the few municipalities that refused to take part in the ‘Sweden-wide’ program and has, to date, never accepted any immigration program in exchange for state provided monetary incentives. The adamancy with which this municipality wishes to conserve its native heritage was put on display when The Local reported on an incident that took place in December 2008. A local politician chose to resign after having his property vandalized and receiving threats for proposing the municipality accept three unaccompanied child refugees. He received a picture of the 2007 Rosengård fires suggesting he wished to transform Vellinge into the next Rosengård. In one of the letters he received it was written that, “in states with law and order they get rid of people like you” (The Local 2009).

This municipality has the highest support in local elections for the Moderate Party, the most opposed to the Swedish integration and immigration policies. Strangely, however, in statewide elections the municipality tends to vote for the Social Democrats, a far more liberal party in regards to immigration (The Local 2009).

Immigrants Associated with Crime and Violence

The native population has long since thought of immigrant populations and communities in Sweden as an engine churning out individuals destined to be responsible for the state’s future criminal activity and violence. Immigrants and those born in Sweden to one or more immigrant parents are proportionally over-represented in criminal activity within the kingdom. This group is statistically responsible for represent 45 percent of Sweden’s crime (The Local 2005). It is precisely for this reason that Frederek, a native Swede and resident of Vellinge, is opposed to opening up the municipality to refugees.

Frederek, a 64-year-old financial advisor, exudes ‘Swedish’. His tall physique is emphasized by good posture and bright blue eyes magnified by bifocal lenses. He spoke a great deal about the importance of tradition in his country and the necessity for it in order to maintain the Swedish way of life. “We are a peaceful people,” he expresses, “we wish to work and live full happy lives.” Though he expresses understanding and sympathy for the situation in Iraq, he believes that it is “no excuse to bring crime [to Sweden].”

Frederek is a big believer in the principle ideology of the Swedish welfare system. He believes that immigrant populations, who have no interest in finding a way to live peacefully in Sweden, repeatedly violate one of the primary principles, partnership. This belief is especially targeted at immigrants entering from non-European countries. He went on to explain that these cultures are in direct opposition to the Swedish way of life and they [non-European immigrants] have no interest in becoming more Swedish or at least adopting some of the basic ideas. Frederek is sure to clarify that he does believe Sweden is doing a good thing by taking in refugees because all people should have a safe place to live and raise a family but the recent outbreaks of violence in Rosengård have only strengthened his support in the local Moderate Party (the most anti-immigration party). He finds the constant clashes with police and riots to be signs that this group is ungrateful and though he does not believe this to be true of all immigrants, he does believe that it is enough of them to want to keep them out of Vellinge.

“If there is a dispute between neighbors, we talk about it or sometimes yell. But we are never burning up cars and buildings,” Frederek addresses the different cultural approaches to frustrations. He also noted that if Swedes wanted a policy change, they would vote on it. He believes that violence is a way of life for many people of the world, especially the Middle East, and that it has no place in Sweden.

The majority of Swedes I interviewed recognized a need to shelter refugees coming from the world’s conflict zones. Many also felt, however, that the refugees and immigrants were responsible for much of the countries crimes. In line with Frederek, many found the cultures of refugees coming from outside of Europe, to be too dissimilar. Their apparent unwillingness to adopt Swedish values lead to culture clashes in which they, the immigrant populations, resolved with violence rather than peaceful negotiations or democratic practices.

Rosengård, in particular, was used as an example to show that Iraqis were unable to solve conflicts or unsatisfactory situations peacefully. “Car explodes on Rosengård,” “Rioting breaks out in Malmö suburb,” and “Fire-fighters given police escort to rowdy Malmö suburb” are just a few of the headlines Swedes have been reading about Rosengård. Though unrest in the suburb has been on the rise, this is by and large the only side of the community Swedes are being exposed to through the media. Located only forty minutes by car from Vellinge, these reports have strongly discouraged any kind of opinion change in the exclusion of immigrants from the municipality.

Just not ‘Swedish Enough’

The section above touched on the idea that Iraqis just are not ‘Swedish enough’. For many Swedes, it seems that for a group to be integrated they have to be all but assimilated into the culture. The opposition to learning the Swedish language or adopting Swedish customs was brought up in almost every interview. Everything is thought to be different, from the earlier bedtime of the typical Swede verses the typical Iraqi to the fact that Swedish police had to issue tickets and fines to immigrant drivers to stop them from honking in neighborhoods. Though neither is a right or wrong way of going about life, it is felt that because Iraqis are guests in Sweden, they should be open to the adoption of some of there beliefs.

When I questioned interviewees on if they believed religion was any kind of contributor to the constant head butting going on between the two cultures I was started that the majority of them believed that Iraqis were almost one hundred percent Muslim. In the past two years or so, Islamic refugees have grown in number in Sweden but many of the Iraqis in Sweden are Assyrian Christians and have had established churches in Sweden for decades. Misconceptions on the issue of Islamic fundamentalism and its prevalence among Iraqis were also commonly expressed. This may be due in part to the lack of exposure to Muslims in the past. The Swedish census of 1930 identified only 15 Muslims, while the population today is estimated at 350,000-400,000 (Larsson 2009:56) Ironically, most of the Muslims living in Sweden tend to be secular rather than fundamentalist or hard-lined.

The Swedish people also have a strong belief in the working of the State through employment that many immigrants, in particular those who choose not to learn Swedish but wish to reside in the country permanently, fail to share. Employment is what “makes a Swede a Swede,” clarified Lena, a 46-year-old resident of Vellinge. The Swedish welfare model is not just a model created by and enforced by the Swedish government. It is a mentality engrained in the people of Sweden that everybody contributes to social security so that, when in need, they will be taken care of. Lena went on to explain that she finds employment the keystone to showing immigrants the Swedish sense of solidarity, especially to those who have only experienced different governmental systems such as the former dictatorship in Iraq. She believes, like many other Swedes, that the system must remain a “two-way street”; Sweden helps people, but it is expected that all will help contribute to the system.

Failure of Integration Policy

For many Swedes the difficulty with the integration of Iraqis is a failure in the state’s integration policies themselves. The list of grievances with the system is endless. The inability of the Swedish government to persuade Iraqis to move away from their place of entry or already overcrowded metropolitan areas is a huge complaint. “We must all be equal but you see twenty people living in one apartment, no one with job,” Jörgen, a 77-year-old farmer supporter of Sweden’s open boarder policy to refugees. Jörgen like many Swedes with which I spoke believes that if Sweden wishes to commit to helping in the humanitarian crisis they must be able to properly integrate the population. By properly integrate, they mean more then just integration into the labor market; they mean that refugees deserve the right to have the same standard of living as Swedes as well.

The enormous failure, as many describe it, in dispersal among Iraqi refugees is regrettably creating a sort of Iraqi ghetto in places such as Rosengård and Södertälje. The dispersal issue starts a chain reaction of consequent failures that is ordered something like this: a failure to disperse the Iraqi people leads to overcrowding; the overcrowding leads to poor living conditions and lack of available space in language learning courses: the inability to learn Swedish keeps Iraqis (even the well-educated) from interacting with native Swedes and landing permanent jobs; without native interaction the community remains segregated and marginalized and without a permanent job they are unable to financially support themselves or their families; if they are unable to support themselves or their family they are financially reliant on the state, not contributing to the state, and unable to move away from the overcrowded city.

These are the conclusions many of the Swedes had drawn from what they have learned about the Iraqi situation in Sweden. “They come here for help and we put them in bad situations,” Lena, Frederek’s wife, stated.

Issues raised by Iraqis

My time in Rosengård was spent in order to find the complications and obstacles, as seen by the Iraqi refugees residing here, which are hindering the integration of this population into Swedish Society. Through interviews, conversations, observations and fleeting encounters, I collected data on the dilemma. The majority of my informants were middle-aged married women, most of who had come over within the past year or so to reunite their family with the male provider who had arrived ahead of them. I was also able to conduct a formal interview with one male adult and several children. My data have been collected from a very small group of individuals residing in the Malmö suburb of Rosengård. Here 84% of the population is either foreign born or second generation. The information I was able to gather from this particular set of informants highlights the basic issues I drew out from my research through personal stories in regards to the integration difficulties they are experiencing.

Upon arrival in Sweden, its characteristic calm and placidity, even in the large metropolitan city of Malmö, struck individual Iraqis immediately. Families and individuals coming from cities such as Mosul and Baghdad were especially sensitive to the obvious audible difference in everyday life. Cities they once called home were described to me as chaotic, noisy and full of shouting and traffic during the day. At night there were only sounds of the few who dared to venture out during the hours after the curfew took effect. The sounds of these individuals were superimposed by the relative frequency of gunshots, bombings and/or screams. Though many of these sounds were common, they are not something any of the citizens could become fully acclimated to. “You can never tell how far away these noises8 are,” Fatima, a 36-year-old, mother of three, told me. The tense state, in which many lived, exhausted individuals, some to the point of debilitation. They found the constant “on edge” feeling in a place they called home nothing short of tortuous.

This is a photograph of one of the many housing complexes located in Rosengård

This is all in comparison to the suburb of Rosengård. Here the apartment buildings are tall gray barrack-like towers with well-manicured lawns. Inside, the moderate sized apartments (most commonly three bedrooms and a kitchen) house extended families and friends, sometimes up to fifteen in one unit. The shops have signs with writing in both Arabic and Swedish (although words are often misspelled and grammar misused.) The suburb is located in the heart of Malmö and is packed with the world’s refugees and their Sweden-born children. Each ethnic group has prominently marked its territory by the flags of their native country hanging in shop windows alongside the Swedish. The residential segregation is markedly noticeable.

The sound of the Iraqi residential area can almost always be attributed to the noise of traffic from the nearby highway, the wind off the Oresund9 whipping through the buildings or the sounds of children playing outside as their parents immerse themselves in conversations about current events and the latest gossip. The atmosphere of Rosengård in comparison to the turmoil in Iraq allows many of the new immigrants to sleep a little more soundly at night. “It is quiet here,” Fatimah, a stout mother of three shares, “I sleep without fear that my family will be hurt.”

Although it is completely foreign in most respects, the knowledge that one is no longer constantly in harm’s way or being targeted by threats of violence has brought about feelings of nostalgia for those who can remember taking that feeling for granted.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Not all have found relief from the war despite the extreme relocation. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a major issue plaguing the Iraqi immigrants. Though unable to find any statistical information specific to this population, it became very apparent during my research that this was an illness affecting a great many of Iraqi refugees. Throughout interviews and informal discussions the prevalence of depression and emotional vacancy among adults was often brought up. Instances of domestic violence as well as failed marriages are common according to Fatimah. “I hear of husband[s] who can not get out of bed in [the] morning and mothers who abuse their children,” she said nervously.

The cause of the illness was thought to be more than just the effects of the war. The loss of one’s home can be terribly traumatic; this combined with the relocation to a foreign country in which relatively everything is strange and foreign to you has sent many into a state of inaction. Though Sweden does offer a number of resources, such as counseling and reception events for just such reasons it has become impossible to provide for all those in need.

Unfortunately, children also display signs PTSD. Behavioral and social problems among children are not uncommon. All four of the women I formally interviewed had stories to tell about their own children on top of the numerous ones they had heard through the ‘grape-vine’.

Safia, a 33-year-old mother of four, moved to Sweden in February 2006. She, and her children, spent two days standing shoulder to shoulder with equally desperate ex-patriots on a small boat to get out of Iraq and into Sweden. Safia spoke often of the fears she possessed for the health and well being of her children. She hoped that they would be able to forget the traumas or at least emerge relatively unscathed from them. Unfortunately this has not been the case. Her two oldest, 13-year-old twin boys are often angry and distant from Safia and the rest of her family. She believes they are involved in a local neighborhood gang that has been rumored to be responsible for a number of vandalism related crimes in the ethnically diverse neighboring communities as well as the harassment of Swedish natives. Her two youngest children, daughters aged 9-years-old and 7-years-old both have severe sleeping and social problems. Nightmares and bedwetting with both happen several times a week. Desperation written all over her face, Safia cried as she talked about how her youngest would wake up terrified and drenched in tears. She described her family as having been broken apart like and egg and she was trying to put it back together knowing it would never fit just right again.

Though most of my informants were mothers, the frequency with which children and the effects of the war and loss of their home, was brought up into conversation, was startling. The harm that had been caused to their children and children’s development bothered seemed to have a constant presence in their conscience. PTSD in children may have strong affects on their ability to achieve any kind of normalcy in family life or otherwise. Also, it can hinder their ability to receive an education or socialize properly.

Marginalization, Social Exclusion and Unemployment

For most of my interviewees, arriving in Sweden was far less burdensome. Those whom I spoke most in detail with came knowing where they would be living because they fell in under the category of family reunification; this is in opposition to individual refugees starting fresh in Sweden. The only interviewee who had arrived as an individual spoke very little about the months he spent in the refugee camps and the resettlement process. He offered only that he knew relatives that were residing in Rosengård. As for the others, they knew where they were headed before they stepped foot on Swedish soil.

Within Rosengård, the population of Swedish natives has dropped dramatically since the 1960s and 1970s when new high-rises where slapped together to help house the large amount of immigrants entering the country. Today the lines between the different ethnically defined communities are almost visible. For those who do not find work to venture outside these communities find little reason to. Therefore, the majority of refugees experience little if any exposure to Swedish society.

Language programs are offered by the Swedish government as part of its comprehensive integration efforts. Today, however, these courses are full to capacity. Primarily males are in attendance; “they are looking for job,” Sait explains.

Sait is a 42-year-old Assyrian Christian and native of Mosul. He left Iraq, ahead of his wife and four children, after receiving death threats. He spoke of the hardships as intolerance and threats of violence affected his family. They were avoided by their neighbors for their religion and his wife was forced to wear a hijab when going to church to avoid suspicion. As the threats became more intense and vandalism to his home began he saw it absolutely necessary to move his family from Iraq as soon as possible. Possessing a PhD in civil engineering, Sait believed he would have little trouble finding work in any country.

Sait came to Sweden in May 2006. After waiting in a camp for more than four months he was able to reunite with distant relative in Rosengård where he continued on with his language programs he had begun in the camps. He has since applied to countless jobs and for the ones in which he is granted an interview he has been refused for insufficient knowledge of the Swedish language.

Sait recalled an interview in which he felt that he had not received a serious interview. Feeling that he knew fully well that he would not be offered the job he pressed the interviewer to tell him why he would not get the job. He was told that, once again, he did not have sufficient knowledge of the Swedish language and therefore could not fully understand the Swedish people. Essentially he was not “Swedish enough”.

This notion was confirmed in my interviews with Swedes, which I discussed earlier. However, becoming “Swedish enough” or even learning the language is not a goal of many Iraqi refugees in Sweden. Some believe that the situation is only temporary and have found comfort in the quiet life Sweden provides without feeling the need to integrate themselves into society. Pickled herring for breakfast and going to bed by 9 P.M. does not appeal to everyone.

Those who do wish to make a new life in Sweden and find value in the ideology of the welfare system must find work in order to give back to the system. However, in order to get a job in Sweden one must master the Swedish language. Like any national language, it is a necessity if one wishes to become an active participant. The language program offered by the state is insufficient without proper exposure to Swedish society. Full immersion in a culture is the best way to learn the language as well as its culture. Unfortunately, for many living and working (if they are able to find work) in over-crowded suburbs, they have little opportunity to interact with Swedes on a daily basis. Many of them feel nervous and as if natives, when venturing outside Rosengård, are scrutinizing them. This discourages proper exposure, interaction and integration into the society.

Beyond the language barrier the lack of interaction between Iraqis and Swedes leads to an ‘othering’ of one another. In general it is easy to tell an Iraqi from a native Swede based on phenotypic traits. This, combined with a difference in style of dress and cultural practices, brings about the creation of stereotypes. The making of these often completely off base generalizations can lead people to false assumptions about and individual or people. “We [Middle Easterners] are all seen as the same [by native-Swedes]. I am not Pakistani or Iranian. I am Iraqi and Christian,” Sait expressed.

The Iraqi refugees shared numerous grievances pertaining to what they believed were the Swedish peoples’ assumptions. Most came from personal experience or stories friends and family had shared. The beliefs that all Iraqis are Muslim, that they all have innumerable children, are prone to violence, uneducated and treat their women poorly were the complaints I heard most about in conducting my interviews. Complaints of discrimination where also reported most notable in the job market.

Wassan, a 26-year-old woman living in a three-bedroom apartment with nine other family members, spoke of a relative who had received his higher education in Sweden. Her uncle, who had come to Sweden in 1994, received a Masters in Cognitive Science from the Lund University, a Swedish institution, in 2002. He is fluent in Swedish and took all of his classes without aid of any translator, Wassan reported. Since receiving his education he has been unable to find a permanent job that he is not overqualified for. Wassan believes that potential employers are discriminating against him.

There have been many studies done pertaining to nearly this exact issue. The International Labor Office conducted a synthesis report published in December 2006 entitled “Discrimination against native Swedes of immigrant origin in access to employment” that focused in high immigrant areas such as Stockholm, Malmö and Göthenburg. Though most address the issue of discrimination against second generation Swedes of immigrant origins, it has been shown that employers are often screening applications based on the name on the application. The difficulties of being an already marginalized population are only escalated when individuals who believe they have met all the qualifications needed to participate in Swedish society are never permitted entry. Not only is this demoralizing but it can easily breed resentment and hostility.

The Specific Role of Unemployment

Due to discrimination and the language barrier it is extremely difficult for Iraqi’s living in Rosengård to find any permanent work outside of their own community. Often employers will not call an applicant after noticing their foreign name (Triandafyllidou/Gropas 2007). Because Rosengård is so densely populated, finding a job within the community is difficult.

Though the SIB overseas the reception programs and job placement for refugees, they have proven unsuccessful in placing refugees with permanent work. Many are hired at jobs well below their skill level. This can be frustrating as Hilda, a tiny but robust woman with deceptively young features for her 64 years explained.

Hilda has been living in Sweden for 14 years. She came over in 1995 to escape persecution of Saddam Hussein’s Baath party. Her late husband, a family physician in Iraq, spent his ten years in Sweden essentially unemployed. They moved several times in search of work but were unable to find anything permanent. He worked many temporary cleaning jobs but the two of them never achieved financial independence from the state.